The Return of Stormont: A Revitalised Government

March 7, 2024

In the recent resurgence of power-sharing at Stormont, a much-anticipated development unfolded as the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) ceased its protest against Parliament, grounded in concerns over the Northern Ireland protocol post-Brexit. As parliamentary activities resume, there are various questions to consider. How did we arrive here? What does it mean? And what is to come?

The chambers of the Northern Ireland Assembly in the Stormont region of East Belfast fell silent in May 2022, marking almost two years of legislative hiatus due to the rejection of the Northern Ireland protocol. The lack of action is undeniably disconcerting, but it is not the first time nor the longest period over which it has occurred, previous suspensions elapsed from 2017-2020 as well as 2002-2007, making a simple 21 month break somewhat of a relief.

On January 30th, DUP leader Jeffrey Donaldson made a pivotal announcement – the restoration of an executive government led by Michelle O’Neill and Emma Little-Pengelly. The catalyst for this breakthrough was the unveiling of the command paper titled "Safeguarding the Union". This comprehensive document aims to streamline domestic imports and foster trade between Great Britain and Northern Ireland, effectively maximising flexibility under the EU/UK deal. A notable outcome of this initiative is the assurance that no routine checks on goods moving between GB and NI will be imposed.

For the first time since Stormont’s founding, Sinn Fein will make up the majority of the assembly. While the first and deputy first ministers share equal power, the historic appointment of Michelle O’Neill as the first republican leader of Northern Ireland carries profound symbolic weight. Mary Lou McDonald, the party leader, claimed last week that Irish unity is within touching distance. While cautioning against undue optimism, the palpable move is noteworthy, particularly given Sinn Féin's popularity in the Republic of Ireland, where an election is anticipated within the next year.

Unsurprisingly, there is a long list of things to do after nearly two years of political paralysis.The UK has offered a £3.3 billion package to stabilise Northern Ireland’s finances which should kickstart some progress. Civil servants, who admirably held the fort during the political impasse, now await the return of elected legislators to fully address the backlog of issues. Resolving public sector pay, exacerbated by a mid-January walkout of 100,000 workers, emerges as an urgent priority. The healthcare sector, mirroring England's struggles, grapples with 79% of patients on waiting lists, significantly surpassing the average in England of 43%. This starkly underscores the detrimental impact of a non-functional legislative body on essential public services.

From the vantage point of the Good Friday Agreement, there emerges significant room for optimism. The agreement, firmly anchored in the principles of power-sharing between unionist and nationalist communities, finds renewed expression in the reunion of an executive government comprising such parties. This, coupled with the restoration of a more stable political environment, propels Northern Ireland toward a governance structure

reflective of the values envisioned by the agreement. As Stormont reengages in political discourse and decision-making, the potential for constructive dialogue, collaborative governance, and positive change beckons on the horizon.

April 2, 2025

Mental Health Support Worker (Post is for a one year contract - further funding might be available after one year subject to additional grant aid). Salary: £10,000 per year – 15 hours per-week 10-4pm Monday, Wednesday and Thursday (excluding lunch). Location: Eaton House, 1, Eaton Road Near Coventry City Centre. Established in 1993, Coventry Irish Society (CIS) is a Charity providing a wide range of community health and support services to the Irish community in Coventry. The Coventry Irish Society requires a Mental Health Support Worker to set up, organise and run a half day per-week Dementia Support Group and a half day per- week Walking Group for the local Irish Community. The role includes working with Carers and increasing mental health awareness to support the local Irish community. The charity predominantly supports older Irish but also supports Second and Third Generation Irish, Irish Survivors and Irish Travellers. . Please email your up to date CV with a cover letter clearly detailing your relevant experience in line with requirements of the role. A CV without an accompanying cover letter will not be accepted. simon.mccarthy@covirishsoc.org.uk or email Simon for further information. Actively interviewing. We reserve the right to close this vacancy early. We are obliged to ask all successful applicants to complete a DBS Disclosure form

By Simon McCarthy

•

March 7, 2025

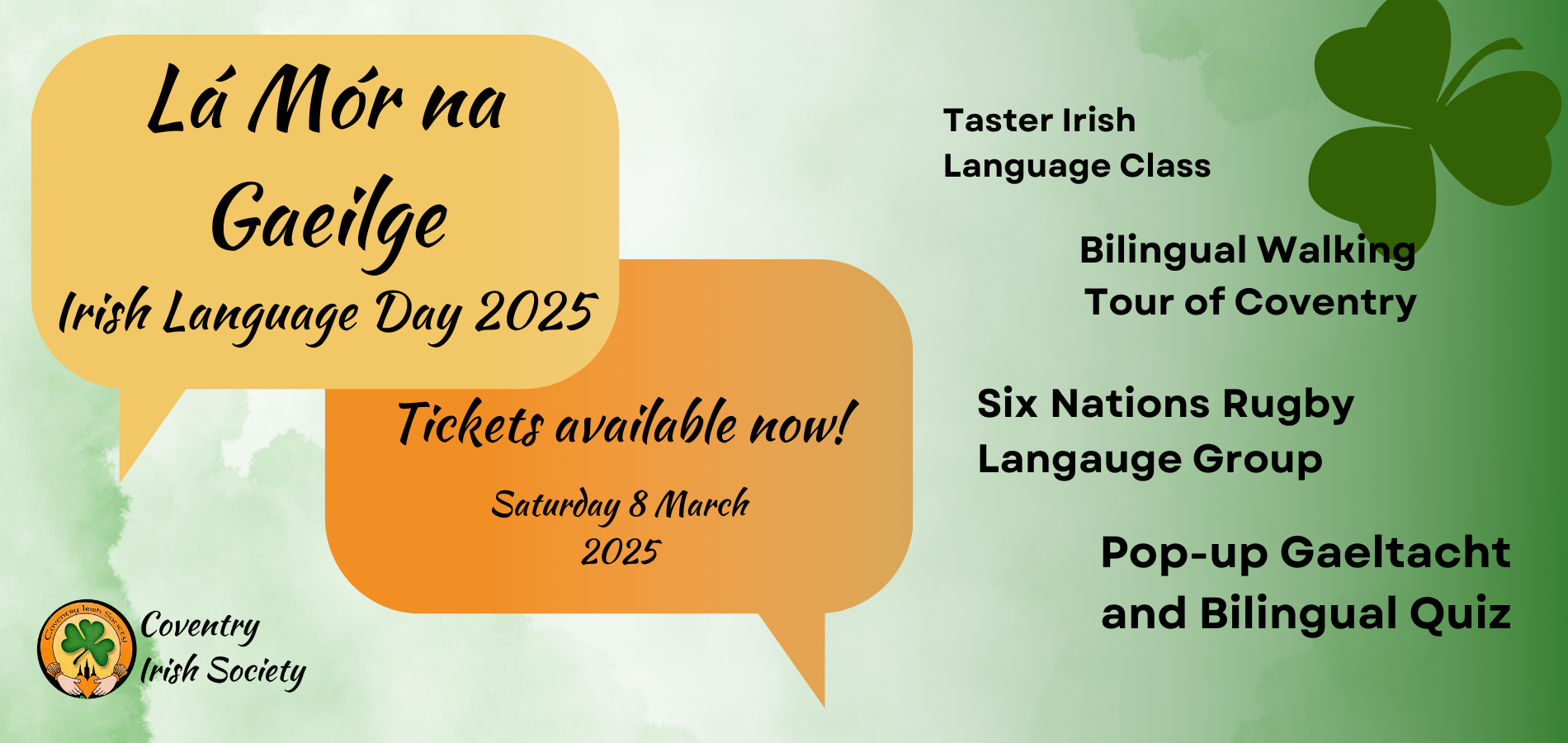

Events with Coventry Irish society include: Irish Language Day | Saturday 8 March St. Patrick's Coffee Morning | Friday 14 March St. Patrick's Family Day | Sunday 16 March Lunch Club | Monday 17 March PLUS...many more! Click below to see the full programme of events across the city.

January 24, 2025

The Coventry Irish Society are delighted to open registration for this year’s Lá na Gaeilge / Irish Language Day which will take place on Saturday 8 March 2025, for all levels, as part of the Coventry Irish Society’s St Patrick’s Festival and Seachtain na Gaeilge 2025 (Irish language week). 1. Taster Irish Language Class Áit / Location: Ground Floor, Quaker Meeting House, Hill Street, Coventry CV1 4AN Arrival: 9.15 – 9.25 am Session ends approximately 11.10 am to allow a short break before the next activity. The group are welcome to stay together, on location, during the break. Múinteoir / Teacher: Nollaig Doughan The session will be suitable for all levels and will include various activities, including the opportunity to learn the Irish National Anthem, as Gaeilge (which might come in handy for the rugby later!). 2. Síulóid / Bilingual Walking Tour of Coventry 12.00: A fascinating síulóid /walking tour around historical city centre sites will be led by Christy Evans and will take approximately one hour. Christy writes a column, in Irish, for The Irish World. Christy is a gaeilgeoir and has dedicated his life to teaching and promoting Irish. His notable achievements include being the European Commission Language Ambassador for Irish, Winner of The Pride of Ireland Award 2007, and Founder of Coláiste na nGael. Coláiste na nGael - Wikipedia Christy has written a short Irish / English guide booklet on Coventry and this will be provided to participants on the day. The meeting point and end location are TBC, but will be around the Cathedral / Broadgate area of Coventry. Adults booked on the tour may bring children with them, free of charge (1x child per parent / guardian / carer who is fully responsible for the child’s supervision and care at all times). Please ensure that a child’s place is booked in advance, at the same time as purchasing the adult’s ticket. Attendees should wear comfortable footwear and suitable outdoor clothing as this will be an outdoor event. They may also wish to bring a drink / light snack. 3. Free-time or option to join the language group for the Six Nations Rugby (Ireland v France) Áit / location: The Hearsall Inn, Craven Street, Coventry CV5 8DS Am / Time: approximately 1.45 pm – 4.15 pm. This part of the day is not formally organised by the Coventry Irish Society and so we cannot reserve seating (or control the result!!), but we do hope that Irish speakers will stay together to keep speaking Irish and to sing the Anthem, as Gaeilge! 4. 7.00 pm Pop Up Gaeltacht & Bilingual Quiz Áit / Location: The Hearsall Inn, Craven Street, Coventry CV5 8DS Am / Time: 7.00 pm – 9.00 pm Over 18s only Tickets Adult Full Day Ticket £10 members / £12 non-members. This includes the Taster Session, Walking Tour & Evening Quiz. Adult Half Day Ticket £6 members / £8 non-members. This includes the Walking Tour & Evening Quiz. This will be a popular day and advance booking is essential. Places are limited and will be allocated on a first-come, first-serve basis. Tickets do not include food / drink. Admission to watch the rugby game is free. Please contact Caroline Brogan, at caroline.brogan@covirishsoc.org.uk or telephone 024 7625 6629, or visit our office at Eaton House during office hours, to obtain a booking form and arrange advance payment. On receipt of payment, a confirmation email will be sent to you as proof of booking. Leibhéal / Level: The day is suitable for all levels, from fluent speakers, to beginners. Where possible, we will try to tailor the level of Irish to the attendee. All activities will be bilingual.

Your support can make a difference

Consider contributing as little or as much as you can. Every pound donated goes toward keeping our programmes and activities available.

© 2025

All Rights | Coventry Irish Society

Coventry Irish Society is a Registered Charity No. 1150290 : Company Limited by Guarantee No. 8235510

Privacy Statements | Website powered by : Duda Site Builder | Website Developed by : First Stop Web Design

We have taken all steps within our means to ensure this website broadly complies with W3C and The Equality Act standards.