“I’m an ordinary man, nothing special nothing grand I’ve had to work for everything I own

I never asked for a lot, I was happy with what I’d got

Enough to keep my family and my home”

Christy Moore, Ordinary Man

On Sunday December 4th last year, I got to experience a feeling most of us never will. It was then that I stepped over the threshold of the cottage and enter the bedroom in which my father had been born exactly 100 years before.

Built some two centuries and more ago, my family home is one of those ancient Irish cottages that nature cannot shift despite its having been built with no foundations. Jammed into the ground like a building brick abandoned by some giant toddler, the house has long since been declared uninhabitable. Whilst a trifle unnerving, to enter and drink deep of all its history so many years later is a truly life-affirming experience.

Dad was the third of the five children – three brothers and two sisters – who were born in this house; this room; this bed. While quiet, unshowy individuals, all five of them had their own genuinely extraordinary story to tell.

Dad’s eldest brother, Paddy, ran off to sea and circumnavigated the world several times; an adventure – and, who knows, a girl – in every port. His youngest brother, Jimmy, never cared to explore much further than Dublin and became the ‘one who stayed’ to tend the family smallholding. When not tilling fields and tending sheep, he found time to teach himself how to clinker-build rowboats and later sailing dinghies. By the time he died three years ago, he was arguably the finest Irish boat builder of his generation.

MORE…

My aunties, Mary and Kitty also lived long and fulfilling lives. Mary married the eighth-son-of-a-seventh son and raised one son and four daughters. Kitty ended up getting wed to the uncle of the man who headed up the CIA under Barack Obama and had a son of her own.

All bar my Dad, who died in his mid-sixties, and Paddy, who barely scraped into his eighties, lived until well into their tenth decades.

Like so many of those born around the time of the Civil War, mid-1940s Ireland held out few prospects for Dad. Bravely exchanging the bucolic simplicity of his rural childhood for the smoke-belching strangeness of the UK’s industrial heartlands, he embarked on the tricky task of trying to build himself some sort of future.

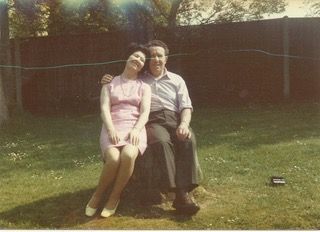

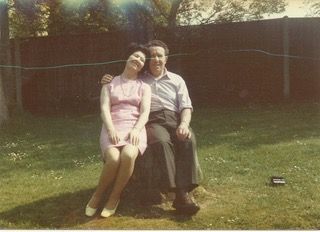

With ‘No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs’ signs a depressingly common sight in the windows of post-war British boarding houses, life for those ‘fresh off the boat’ must have been incredibly dispiriting. After working in Ipswich for a while, he and my Mum eventually married, settled down, moved to Coventry and started a family.

While overseas trips were a luxury few could afford back then, going ‘home’ for the Holiday Fortnight was a yearly ritual for the city’s large Irish diaspora. Dad, Mum, my elder sister, Mary, and myself were no exception. Perched precariously atop cheap cardboard suitcases in the impossibly over-crowded and smoky corridors of boat trains, we’d inch with molasses-like slowness towards Holyhead and the overnight ferry.

Once in Ireland, we would spend the first week of our holiday with Mum’s family near Athlone. The second Saturday marked the start of the happiest days of my childhood:

Seven blissful days in this tiny cottage by the Shannon that I now co-own with my sister and am blessed to be able to visit any time I need to calm and centre myself.

Granted a brief escape from the crushing monotony of factory life for a couple of short weeks, most men would have been content to sit by the turf fire and toast their toes.

Not my Dad.

On the rare days, Roscommon had exhausted its seemingly infinite reservoirs of rain, he’d head across the fields and join his boyhood friends in forking hay into stacks for their livestock’s winter feed. Back and shoulders seared an incandescent red from the sun, he’d later wash up, eat his tea and walk the mile-and-a-half to Coffey’s Bar to sink a couple of well-deserved post-work pints of plain.

To the left of the bedroom in which Dad entered the world is the parlour. In here was located the dresser where my grandparents’ best delft was kept for special occasions. Our annual return ‘home’ was one such event and was invariably marked with a celebratory high tea. To the right is located a cosy living area whose thick stone walls and rudimentary concrete floor served as a kitchen, dining and sitting room all in one.

Sitting here all these years later, it is impossible not to recall images of the smiling faces of the ‘ramblers’ whose happy chatter filled that space with warmth and light long before – and long after – the arrival of mains electricity in the early 1970s.

The years (as years are wont to do) ran away like wild horses over the hills. Family raised and grandkids running round the house, Dad and Mum were preparing for a well-deserved retirement. Having been the first member of my family to ever make it to Uni, I’d followed in Dad’s footsteps and moved overseas to seek my fortune.

All too soon it was August 1988 and Dad and I were standing on the concourse at Coventry Railway Station as I awaited the first leg of the long journey back to Hong Kong. Slowly being eaten away from the inside by the cancers that were killing him and so many of those who worked by his side, Dad looked agonisingly small, shrunken and worn out. Aware as kids often are, I knew I would never see him again, and for the first and last time in my life told him that I loved him. Three short months later he was gone.

That’s not the way I choose to remember Dad, though. My most cherished memory of him is of the many times Mum and I took the train to nearby Birmingham to seek treatment for a medical condition I suffered as a child. Standing impossibly high on the gantry on the side wall of the electroplating factory where he literally worked himself to death for a quarter of a century stood my Dad waving us God speed.

Having attained an age my poor father never managed to reach, here I stand on the threshold of a house whose only contents are memories too cherished to ever fade.

Gently closing and locking the door before heading back to town, I feel humbled by the struggles of all the genuinely remarkable family members on whose shoulders I now stand. While many people have offered to buy this ramshackle house and the windswept riverfront land it stands on, some memories are simply too precious to put a price on.

An earlier version of this article appeared in The Roscommon Herald in December, 2022.

The author has requested that any fees payable for this contribution be donated to Focus Ireland

John Fuery